History

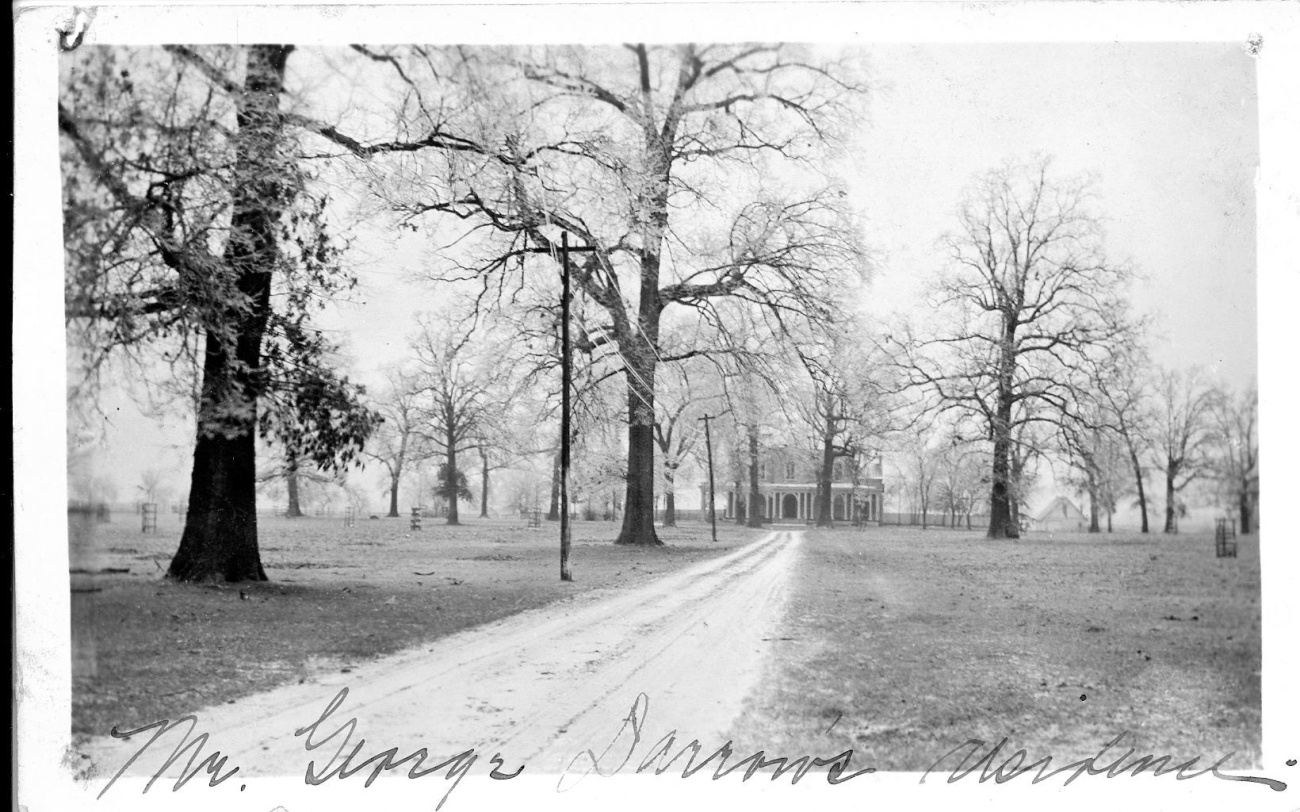

The earliest known photograph of Oaklands Mansion was taken in the winter time, circa 1888, and reads “Mr. George Darrow’s residence.”

Oaklands began in the late eighteen teens when Dr. James Maney and his wife Sallie Murfree Maney moved to Murfreesboro. In 1813, Sallie inherited 274 acres of land north of the town named for her father, Colonel Hardy Murfree. The Maney family then migrated from Maney’s Neck, NC, to Middle Tennessee in the mid Eighteen-teens, forcibly moving eighteen enslaved individuals with them as well. About three generations of enslaved families would eventually live, work, and die at Oaklands. A document from the Williamson County Probate notes that the Maney’s brought the following enslaved individuals with them from North Carolina:

October 1814, Williamson County Probate

Lot #5

- Willie $400

- Selvey, wife and child of Willie $300

- Mogga and daughter $200

- Hardy $200

- Harriett $175

- Henry $150

- Willis $100

- Tim $325

- Tinney and child $275

- Nat, son of Tinney $250

- Warrick, Son of Tinney $212.50

- Dinah, his daughter $150

- Eliza $125

- George Porter and Luckey, his wife $150

- Sam $400

Total Value of lot #5, $3714.37

It was on this tract that the Maneys constructed what would become one of the most elegant homes in Middle Tennessee. The original structure built on this land was a two-room brick house next to a large spring north of Murfreesboro and was built by enslaved people owned by the Maneys.

The two-room house was built on the hall-and-parlor plan, a design that would have been familiar to the Maneys. It was a well-constructed one-and-a-half-story house with dormer windows and a chimney at each end, as well as penciling on the brick mortar to enhance the house’s apperance. At a time when many people lived in log cabins, this small brick house reflected permanence and distinction. Its appearance was enhanced greatly in the 1820s when the Maneys attached a two-story addition, in the Federal style, to the west gable end of the original house. Built by the Maneys enslaved labor force, skilled in carpentry and masonry, the new rooms included a parlor, a front hall passage with a staircase, and a chamber over the parlor that probably served as the Maney’s first guest bedroom. The only access from the old house to the new addition was through a doorway on the first floor. The amount of enslaved individuals the Maney’s owned also increased during the 1820s to at least fifty. Beyond carpentry and masonry, the enslaved individuals also cleared land, planted and harvested crops, and worked in the house.

By 1830, the Maney family at Oaklands was prospering and growing. In the 1830s, their skilled enslaved people added a two-story ell consisting of a dining room on the first floor, and children’s bedrooms directly above and to the rear of the original two-room house. The ceiling height of the original two rooms was then raised to two stories to allow for a more unified roofline, larger second story rooms, and longer windows to bring in more light. By 1840 the enslaved population living on the Oaklands estate grew to nearly one hundred people. Lured by the prospect of richer soils and wealth, Dr. James Maney moved most of his large-scale cash crop operations to his Trio Plantation in the Mississippi Delta in the early 1840s. This move led to the breakup of families and friendships, as nearly half of his enslaved workers were forced to migrate to Mississippi.

Sallie Maney died in 1857 and Dr. James Maney likely retired from his medical practice that same year. He then lived in the various households of his children, as well as his own apartment near downtown Murfreesboro, until his death in 1872. After Sallie’s death, Oaklands then passed into the hands of their son Lewis and daughter-in-law, Rachel Adaline Cannon, though they would not fully gain the deed to Oaklands until Dr. James Maney died in 1872. These second-generation of owners made extensive renovations and additions that brought Oaklands to its present appearance.

These additions were likely constructed sometime between 1857 to 1859. Today the mansion is interpreted primarily to the Maney period of ownership (1815-1884) with an emphasis placed on the late 1850s to1860s time period. Approximately one-third of the furnishings and artifacts are original to the home. While most of these pieces have been donated by Maney, Murfree and Cannon descendants, some items in the collection are from the Darrow, Roberts and Jetton periods of ownership.

Lewis, the son of Dr. James Maney and Sallie Maney, and Adaline, the daughter of former Tennessee governor Newton Cannon, were both accustomed to the privileges that accompanied their elite social status. Aware of the latest fashions in furnishings and architecture, they planned a new Italianate addition that would totally eclipse the old plantation house and make the manor more suitable for lavish entertaining.

The Italianate-styled two-story front addition, designed by prominent local architect Richard Sanders, included a library and a front parlor separated by a hallway on the first floor. At the rear of the front hall, a magnificent cantilever staircase was installed that led to two upstairs guest bedrooms, one above the front parlor and one above the library. A spacious central hall separated these guest bedrooms. The exterior of this section featured a grand arched front entrance on the first floor, heavy window surrounds and hood molding, bracketed eaves, and an elegant second floor window that replicates the arched design of the front entrance directly below. The entire facade was dominated by a verandah of elongated chamfered arches and columns.

It is clear that the Maneys’ lifestyle of leisure and luxury is due in no small part to enslaved workers. Beyond the previous tasks mentioned above, the enslaved also worked as domestic servants. Whitewashed walls and the remains of a bell-ringing device suggest that some domestic workers lived in the basement. By 1860 most of the enslaved families living at Oaklands lived in the nineteen slave dwellings owned by Dr. Maney and his sons. A community emerged that linked the slaves of Oaklands to their friends and family at adjoining and nearby farms. Spence Maney recalled frequently visiting his family members on the neighboring farms owned by Dr. Maney’s sons. Another former slave tells how his father left Oaklands each Saturday night and traveled eight miles to visit him and his mother.

The Maney family did not have much time to enjoy their new home due to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. On July 13, 1862, Confederate cavalrymen under Nathan Bedford Forrest’s command surprised and defeated Union forces under the command of Colonel William Duffield. The Union forces were encamped on the grounds, near the spring and at the courthouse as part of a raid on Union-occupied Murfreesboro. It is said that Lewis and Adeline’s children watched the fighting from the window of the second floor hallway. Union Col. Duffield, commander of the 9th Michigan Infantry Regiment, was wounded in the skirmish and taken into the house, where he was treated by the family. The Maneys would also accept more wounded Union soldiers into their house after the fighting concluded, treating the downstairs of the house as an impromptu field hospital. It has been recounted that these soldiers bled so much that it soaked through the carpets and staining the hardwood floors below.

The Confederates accepted the surrender of Murfreesboro inside the mansion. The town was later reclaimed by the Union after their victory at the December 31-January 2, 1862-63 Battle of Murfreesboro, or Stones River, after which Union forces regained control for the rest of the war.

The Maney family hosted many notable visitors while they resided at Oaklands. The most prominent of these was Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who stayed at Oaklands during his December 12-14, 1862 visit to Murfreesboro. Other visitors included John Bell (who ran against Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas in the 1860 Presidential election), Sarah Childress Polk (the wife of President James K. Polk), naval officer and oceanographer Matthew Fontaine Maury (cousin of Rachel Adeline), Confederate General Braxton Bragg, Major General Leonidas Polk, Brigadier General George Maney (commander of the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment, C.S.A. and cousin of the Oaklands Maneys), and various Union officers.

The Maneys, like many southern planter families, experienced personal and economic hardship as a result of the Civil War. Lewis and Rachel Adeline lost two of their eight children to illness in 1863. The abolition of slavery as a result of the war freed the enslaved people on the Maney’s plantations and greatly diminished their principle source of income. Before the war, the Maneys owned at least two plantations in Mississippi, as well as their plantation on the grounds of Oaklands, and each likely experienced damage during the war, although the extent is not known. In 1872, Dr. Maney filed a claim against the federal government in the amount of $27,012 for property damage and losses incurred at Oaklands during the war as the result of the activities of both armies. The claim was ultimately rejected. To alleviate their post-war financial difficulties, as well as legal troubles, the Maneys sold off portions of their Oaklands landholdings. Two such transactions occurred, resulting in the creation of present-day Maney Avenue and Evergreen Cemetery by 1872.

The Maneys, however, managed to retain partial possession of their Oaklands plantation for almost twenty years following the war. They would not maintain procession of the plantation and the mansion forever, though. In 1884, Rachel Adeline sold the house and 200 acres at public auction to cover the debts of Lewis Maney, who died two years before in 1882. Elizabeth Swoope of Memphis purchased the property. It was later inherited by her brother, Leonidas Hayley, and then, following his death, by Mrs. Swoope’s daughter, Tempe Swoope Darrow. A number of changes, which were mostly interior modernizations such as the addition of electricity and plumbing but did include the addition of a new kitchen and converting the previous kitchen into a garage for their car, were made during the Swoope-Darrow period. When Tempe and her husband, George Darrow, moved to their new home on Main Street in 1912, they sold the house and the remaining acreage to R. B. and Jennie Roberts. Oaklands remained in the Roberts family until 1936 when they sold it to the Jetton family. The Jettons owned the home until 1957. A few years before then, Ms. Rebecca Jetton found the house too large to maintain alone and moved to the James K. Polk Hotel in Murfreesboro.

Thus, from about 1954 to 1959, the mansion was vacant and suffered from both neglect and vandalism. Woodwork, mantels, window frames, and many other architectural features were damaged or stolen. The City of Murfreesboro purchased the property from a local realtor in 1958 and had plans to demolish the site and build low-income housing.

When it became known that the City planned to raze the mansion, a group of ten concerned local women mobilized to save Oaklands from this unceremonious fate. In April 1959, they formed the Oaklands Association and lobbied the City to deed the mansion to them. The City agreed to do so and sold the mansion to the founding ladies for one dollar, with the stipulation that the Association restore the house and open it to the public within ten years. This group of dedicated women, with financial help from local residents, businesses, groups, the State of Tennessee, and various Association-sponsored membership drives and fund raisers, then proceeded with the challenging task of cleaning, rehabilitating, restoring, and refurnishing the house. They were able to restore Oaklands and open it to the public as a house museum in the early 1960s, with the help of free prison labor from the Rutherford County Workhouse in restoring the house. Since then, the Association has directed its energies toward preserving, restoring, interpreting, and maintaining the mansion and its grounds, collections, and furnishings.

Today, Oaklands Mansion strives to preserve the Mansion and its grounds and interpret the two centuries of history at this site for diverse audiences. Oaklands welcomes thousands of visitors each year, including special tour groups, school children from Rutherford and surrounding counties, and people from all states and many foreign countries.